Recently, I decided to learn more about the economic history of Venezuela, especially the Chávez-Maduro period. I took some notes in the process, and thought they might be of use for others. In this post I will try to paint a rudimentary picture of Venezuela’s contemporary economic history using the sources that I read. To be clear, except for the concluding part, I mostly quote the original authors, so any credit goes to them. This is also by no means an exhaustive account, and only includes certain aspects of the story that I found more interesting. I tried to arrange the excerpts from original sources in a way that would be intelligible, but you can escape my notes and only read those sources.

There are various reasons why Venezuela is an interesting case. For one, as a left-leaning economics student, learning from the lessons of Venezuela’s failed “socialist” experiment seems essential to me. “Venezuela! Venezuela! Venezuela!” might be an overused slogan on the right when responding to any modestly social-democratic program on the left, but that should not compel leftists to glibly discard the case of Venezuela without figuring out precisely what went wrong there. Moreover, there are striking similarities between Venezuela and my own country, Iran. Both are authoritarian petrostates with large interventionist governments, have relatively unequal income and wealth distributions, and are geopolitically opposed to the United States. More generally, it seems to me that any commodity-producing nation would do well to learn from Venezuela’s economic mistakes.

Readings:

Restuccio, D. (2022). The History of Venezuela. A Monetary and Fiscal History of Latin America, 1960–2017, edited by Timothy Kehoe and Juan Pablo Nicolini, University of Minnesota Press

Perri, F. (2022). Discussion of the History of Venezuela 2. A Monetary and Fiscal History of Latin America, 1960–2017, edited by Timothy Kehoe and Juan Pablo Nicolini, University of Minnesota Press

Hausmann, R. (2017). Venezuela’s Unprecedented Collapse. Project Syndicate

Hausmann, R., & Rodríguez, F. (2014). Venezuela Before Chávez: Anatomy of an Economic Collapse. Preface, Introduction, and Chapter 1, 8-63. The Pennsylvania State University Press

Bacha, E., & Fishlow, A. (2011). The Recent Commodity Price Boom and Latin American Growth. The Oxford Handbook of Latin American Economics, edited by José Antonio Ocampo and Jaime Ros, Oxford University Press

Weisbrot, M., & Sandoval, L. (2007). The Venezuelan Economy in the Chávez Years. Center for Economic and Policy Research

Venezuela before Chávez:

The reversal of fortunes:

Ricardo Hausmann (2014): “The twentieth century saw the transformation of Venezuela from one of the poorest to one of the richest economies in Latin America. Between 1900 and 1920, per capita GDP had grown at a rate of barely 1.8 percent; between 1920 and 1948, it grew at 6.8 percent per annum. By 1958, per capita GDP was 4.8 times what it would have been had Venezuela had the average growth rate of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru (calculations based on Maddison 2001). By 1970, Venezuela had become the richest country in Latin America and one of the twenty richest countries in the world, with a per capita GDP higher than Spain, Greece, and Israel and only 13 percent lower than that of the United Kingdom”

Diego Restuccia (2022): “In the postwar era, Venezuela represents one of the most dramatic growth experiences in the world. Measured as real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in international dollars, Venezuela attained levels of more than 80 percent of that of the United States by the end of 1960. It has also experienced one of the most dramatic declines, with levels of relative real GDP per capita now reaching less than 30 percent of that of the United States.”

Why did Venezuelan growth collapse?

Ricardo Hausmann (2014): “Venezuela’s growth performance can be accounted for as the consequence of three forces. One is declining oil production. The second is declining non-oil productivity. The third is the incapacity of the economy to move resources into alternative industries as a response to the decline in oil rents that has occurred since the seventies […] The authors then concentrate on this second factor, asking why Venezuela found it so difficult to develop an alternative export industry, in contrast to other countries that suffered declines in their traditional exports. Their answer is that Venezuela’s concentration in oil puts it in a particularly difficult position because of an idiosyncratic characteristic of the oil industry: the specialized inputs, knowledge, and institutions necessary to produce oil efficiently are not very valuable for the production of other goods.”

The reliance of the Venezuelan economy on oil:

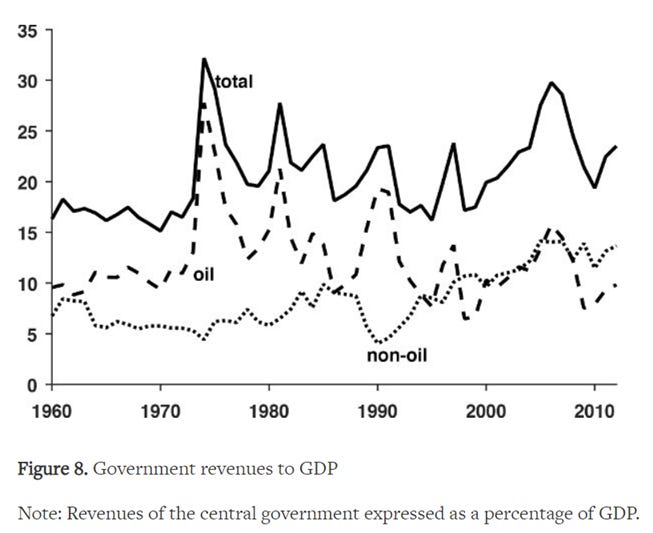

Diego Restuccia (2022): “Venezuela […] today has one of the largest proven oil reserves in the world. During the 1920s, oil production, at the time mostly done through concessions to foreign companies, was an important contributor to Venezuela’s structural transformation and development. Over time, discussions about the nationalization of the oil industry in the late 1960s and early 1970s brought a halt to this development even though nationalization was only formalized in 1976. For instance, total crude oil production declined substantially (55 percent) from its peak in 1970 to the mid-1980s, and labor productivity in the oil industry declined by more than 70 percent in that period […] Oil represents an average of around 90 percent of all exports and almost 60 percent of government revenues during the period between 1960 and 2016.”

Is the Venezuelan experience an instance of resource curse?

Fabrizio Perri (2022): “Venezuela’s growth disaster after the 1970s is often cited as a textbook example of the so-called resources curse […] One caveat for this interpretation is that oil in Venezuela was discovered and developed early (in the 1920s), and, from 1930 to the 1970s, abundant oil resources have been associated with Venezuela’s fast growth. Venezuela thus serves as an example of both a resources blessing and a resources curse. Indeed, as noted in Torvik (2009), “For every Nigeria or Venezuela there is a Norway or a Botswana.” This is why the resources curse literature is now moving beyond explaining whether resources are good or bad for an economy and toward examining under what conditions resources help growth and under what conditions they hinder it. The evolution of monetary policy […] suggests that resources in Venezuela might have played a different role over time. Early on, oil wealth might have reduced the need for bad policies in a developing economy—as reflected by an inflation well below the Latin American median—and enabled faster growth than other Latin American countries at a similar stage of development. Over time […] the volatile oil wealth might have increased power struggles instead of investment in institutions, which resulted in worse policies, possibly less democratic institutions, and exceptionally poor growth in the second part of the sample.”

Why is it perilous for a country to depend on commodity exports in the first place?

Edmar Bacha and Albert Fishlow (2012): “in a series of recent studies, Lederman and Maloney […] argue that the resource curse — apparent in the simple correlation between specialization and growth — disappears when a measure of export concentration is introduced in the regressions. They thus suggest that the curse is one of lack of diversification, not resources […] From this perspective, the curse would derive not from the nature of the export good but from excessive export concentration and lack of flexibility to shift out of sectors as required by the evolution of world demand and the country’s comparative advantage. Specialization in commodities, however, would seem to have a definitive drawback, as their prices tend to be much more volatile than manufacturing prices, making it difficult to disentangle temporary from permanent price changes, and thus reducing fixed investment and growth. Some authors have thus suggested that it is exactly the volatility of natural resource prices, rather than the trend, that is bad for economic growth […] Furthermore, the volatility of prices and the relative magnitude of the natural-resource sector for many countries imply huge swings in fiscal revenues, invoking all the attendant complexities of public decision-making.”

Chávez’s political emergence was a symptom of previous economic failure:

Ricardo Hausmann (2014): “Hugo Chávez did not come to power in a political vacuum. His radical authoritarian message was capable of striking a deep chord among Venezuelans only after they became convinced that their institutions were incapable of bringing them prosperity or stability. Chávez was only possible after two decades in which living standards fell by more than one-fourth and the country’s political system imploded. In a context of continued economic deterioration and weakened political institutions, there was a clear opening for a political movement that called for radical change. This was the opportunity that Hugo Chávez saw, and took full advantage of, in 1998.”

The Mother of All Commodity Booms:

The oil boom was the largest in Venezuela’s history:

Ricardo Hausmann (2014): “After 1998, the story of chavismo could have been simpler—and shorter. Hugo Chávez’s policies would have wreaked economic havoc in just about any economy, except an economy that saw its terms of trade grow more than sevenfold. In real terms, Venezuelan oil prices had reached their lowest level in nearly three decades—$7.66 a barrel—in the second week of December 1998, the week during which Chávez was first elected to the presidency. Between 1998 and 2011, Venezuela’s terms of trade grew 6.7 times more rapidly than the regional average and 3.1 times more rapidly than Bolivia’s, which had the second-highest terms-of-trade growth in the region. Even after a decline in physical production and exports of oil caused by the systematic overtaxation of the oil industry and the virtual disappearance of non-oil exports, Venezuela’s exports in 2011 were 3.6 times as large as in 1998.”

The honeymoon period of rapid oil-driven growth:

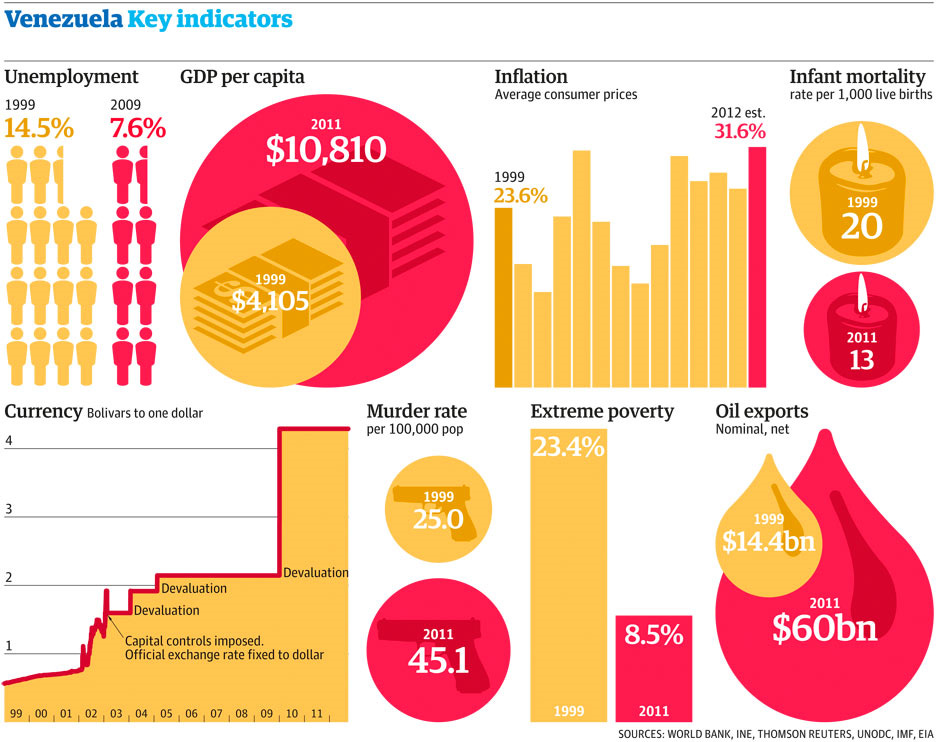

Ricardo Hausmann (2014): “[After the 2002 coup attempt] oil saved the day again, rising from $26 in 2003 to $91.4 in 2008 and $103 by 2012. The resulting windfall dwarfed anything ever experienced in Venezuelan history, including the increase seen in the oil booms of the 1970s and ’80s. This windfall allowed the government to generate a massive increase in its size, which expanded nearly threefold in real terms during Chávez’s tenure in office, growing from 28.8 percent to 41.1 percent of GDP. This enormous expansion in the activities of the state brought about an improvement in many indicators of Venezuelans’ quality of life, such as per capita incomes, poverty rates, and health indicators—though it also coincided with skyrocketing homicide rates.”

Robust growth and social spending by the Chávez government initially brought genuine improvements to the lives of poor Venezuelans:

Mark Weisbrot and Luis Sandoval (2007): “The Chávez government has greatly increased social spending, including spending on health care, subsidized food, and education […] The most pronounced difference has been in the area of health care. In 1998 there were 1,628 primary care physicians for a population of 23.4 million. Today, there are 19,571 for a population of 27 million. In 1998 there were 417 emergency rooms, 74 rehab centers and 1,628 primary care centers compared to 721 emergency rooms, 445 rehab centers and 8,621 primary care centers […] The Venezuelan government has also provided widespread access to subsidized food. By 2006, there were 15,726 stores throughout the country that offered mainly food items at subsidized prices […] These plus expanded special programs for the extremely poor (e.g., soup kitchens and food distribution) benefited an average of 67 percent and 43 percent of the population in 2005 and 2006 respectively […] Access to education has also increased substantially. For example, the number of students in ‘Bolivarian schools’ (primary education) increased from 271,593 for the 1999/2000 school year to 1,098,489 for the 2005/2006 school year.”

It is quite notable that inequality did not decline in the Chávez era (According to data from the World Inequality Database):

Social spending as % of total government spending did not even increase under Chávez, it was just that the increase in oil revenues was so significant the social component of spending skyrocketed as well:

Ricardo Hausmann (2014): “[After the 2002 coup attempt] oil saved the day again, rising from $26 in 2003 to $91.4 in 2008 and $103 by 2012. The resulting windfall dwarfed anything ever experienced in Venezuelan history, including the increase seen in the oil booms of the 1970s and ’80s. This windfall allowed the government to generate a massive increase in its size, which expanded nearly threefold in real terms during Chávez’s tenure in office, growing from 28.8 percent to 41.1 percent of GDP. This enormous expansion in the activities of the state brought about an improvement in many indicators of Venezuelans’ quality of life, such as per capita incomes, poverty rates, and health indicators—though it also coincided with skyrocketing homicide rates. Contrary to popular belief, it was not associated with a change in the priorities of government spending; the fraction of spending devoted to social programs, even after one takes account of off-budget funds, was remarkably stable during Chávez’s administration and not very different from that of previous governments.”

But the results were not even that impressive given the size of the oil boom:

Ricardo Hausmann (2014): “It would have been very hard, in fact, for such a huge oil boom to not have brought about an improvement in Venezuelans’ quality of life, as it in fact did. But the results were lackluster. Venezuela’s drop in poverty rates over this period was actually similar to those of Colombia, Brazil, and Peru, while its growth performance (2.6 percent annual growth since 1998) was the lowest among Latin America’s ten largest economies.”

Macroeconomic mismanagement under Chávez-Maduro:

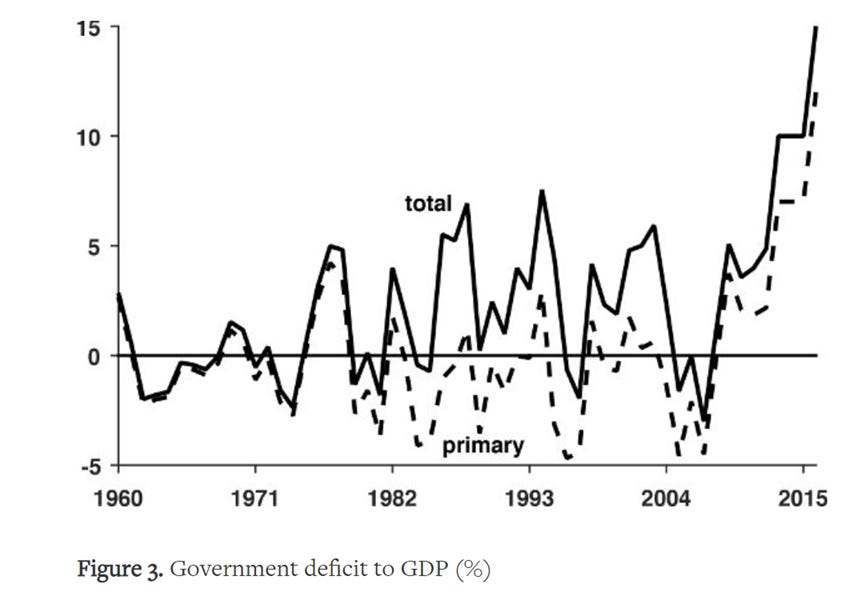

Edmar Bacha and Albert Fishlow (2012): “Much increased expenditures have resulted in persistent fiscal deficits, despite a great rise in governmental revenues. Inflation has threatened to get out of hand. An overvalued fixed exchange rate has had to be devalued, more than once. Multiple exchange rates have returned. Despite curbs on capital outflows, accumulated foreign exchange reserves are seemingly fewer than they should be. A presumed sovereign wealth fund has been utilized elsewhere, in part for non-budgeted outlays, and resources are not available for compensatory fiscal policy. The full extent of the problem has been alleviated by a return to higher petroleum prices in the market.”

Diego Restuccia (2022): “The period between 2006 and 2016 represents a return to large amounts of financing needs on average, with 7.6 pp. Note that this period, like 1975–86, is a period of a substantial and prolonged boom in oil prices. But, distinct from the earlier period, external debt is not a substantial source of financing; instead, seigniorage and especially the inflation tax are the sources that account for all the financing needs, with 1.5 and 7 pp, respectively.”

The collapse after 2013:

Ricardo Hausmann (2017): “The most frequently used indicator to compare recessions is GDP. According to the International Monetary Fund, Venezuela’s GDP in 2017 is 35% below 2013 levels, or 40% in per capita terms. That is a significantly sharper contraction than during the 1929-1933 Great Depression in the United States, when US GDP is estimated to have fallen 28%. It is slightly bigger than the decline in Russia (1990-1994), Cuba (1989-1993), and Albania (1989-1993), but smaller than that experienced by other former Soviet States at the time of transition, such as Georgia, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Ukraine, or war-torn countries such as Liberia (1993), Libya (2011), Rwanda (1994), Iran (1981), and, most recently, South Sudan.”

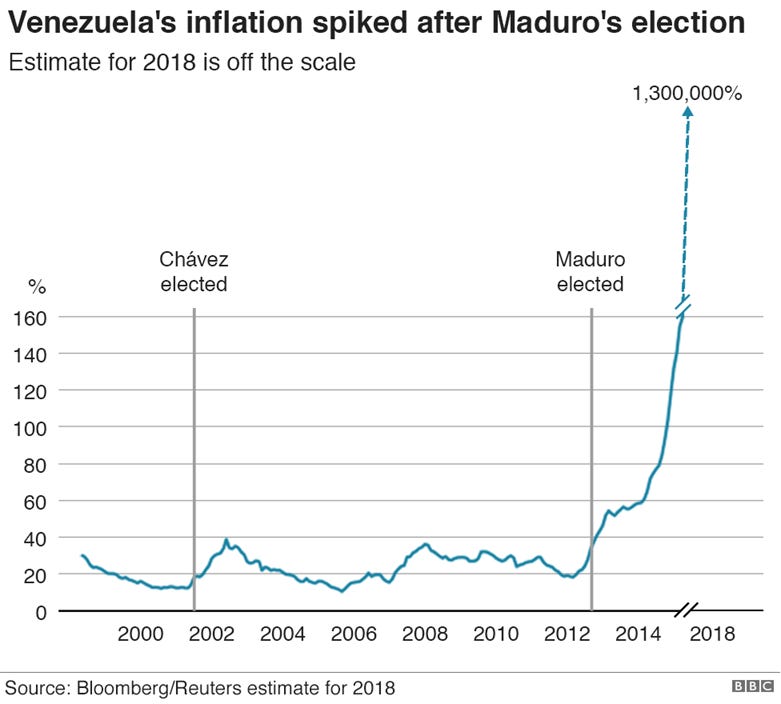

After the fall of oil prices in 2013, the Maduro government resorted to direct monetary financing to fund its rising deficits. Predictably, hyper-inflation followed:

The horrific increase in malnourishment and poverty:

Ricardo Hausmann (2017): “Measured in the cheapest available calorie, the minimum wage declined from 52,854 calories per day to just 7,005 during the same period, a decline of 86.7% and insufficient to feed a family of five, assuming that all the income is spent to buy the cheapest calorie. With their minimum wage, Venezuelans could buy less than a fifth of the food that traditionally poorer Colombians could buy with theirs.

Income poverty increased from 48% in 2014 to 82% in 2016, according to a survey conducted by Venezuela’s three most prestigious universities. The same study found that 74% of Venezuelans involuntarily lost an average of 8.6 kilos in weight. The Venezuelan Health Observatory reports a ten-fold increase in in-patient mortality and a 100-fold increase in the death of newborns in hospitals in 2016.”

Concluding Thoughts:

Venezuela ran fiscal deficits of about 4% during the boom. This was certainly excessive for a middle-income country, and inflation hovered around 30% in this period. As John Maynard Keynes famously said, “The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury”. This is more so for a country that excessively relies on exporting a single commodity, and is thus highly vulnerable to commodity price shocks. Once oil prices crashed, the regime had two choices: either to bite the bullet, significantly reduce government spending and raise taxes, or to continue with business as usual and monetize its ever-increasing deficits. The former would have certainly been unpopular in the short run, so Maduro chose the latter. It certainly did not help that the government aggressively nationalized businesses and tried to use broad price controls to control inflation. The rest is, of course, history.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with trying to address the centuries-long inequalities that are legacy of extractive colonial institutions in Latin America. But the key lesson here is that both the state and the market have a role to play, and macroeconomic prudence is imperative. The long history of unsuccessful attempts at import substitution and nationalization in the region is testament to the former. Though not perfect by any means, episodes of inclusive growth in Bolivia under Morales and Brazil under Lula demonstrate that a center-left pragmatic approach can deliver impressive results. You cannot, however, improve the long-term prospects of poor people by spending every cent during an unprecedented boom. You need to accumulate foreign reserves, invest the revenues wisely in order to diversify your exports, and make sure that government spending is sustainable even if commodity prices plummet. Otherwise, any gain in living standards would be short-lived, as the experience of Venezuela shows.

Would love to read more from you!

سلام خیلی حوب بود ، ببخشید میتونم ایمیلتون رو داشته باشم میخواستم چندتا سوال کوتاه ازتون بپرسم فکر کنم بتونید کمکم کنید